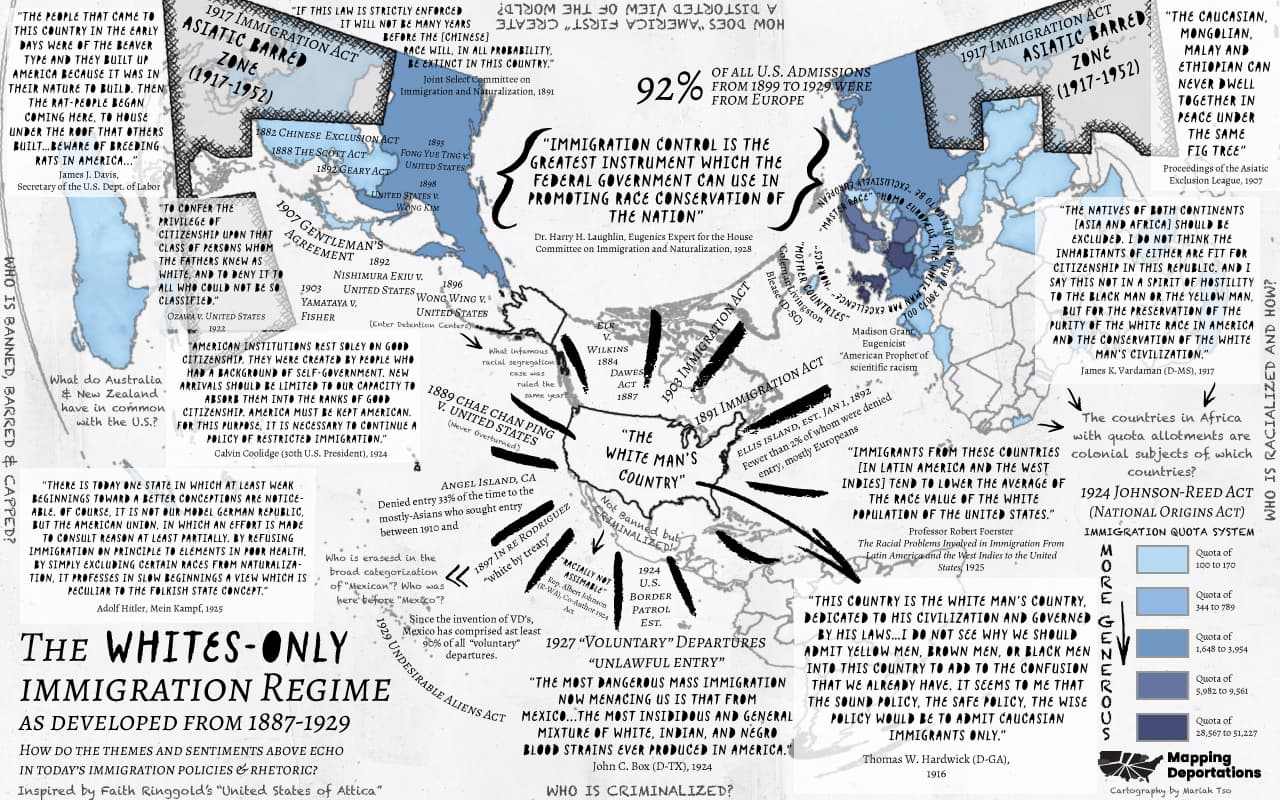

1877-1929

The Whites-Only Regime

After the Civil War, Congress adopted a series of laws designed to exclude, punish, and expel non-white immigrants from the United States. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court declared the U.S. immigration system to be a domain of “absolute” federal governance. By 1929, federal officials had effectively hung a “whites only” sign on the nation’s front door while propping the nation’s “backdoor” open to a structurally marginalized—racialized, criminalized, and deportable—workforce subject to the extraordinary authority of U.S. immigration officials, namely, the U.S. Border Patrol. This scheme was no accident. As the map of quotations below illustrates, federal authorities and prominent advocates of immigration control crafted this “whites-only” immigration regime to simultaneously exclude and subordinate nonwhite immigrants.

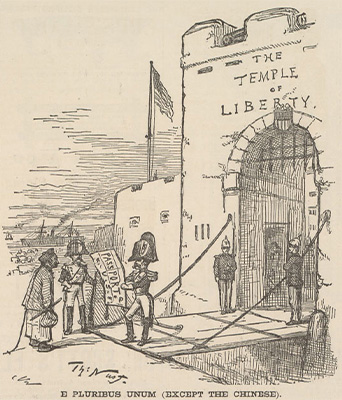

Race and Immigrant Exclusion

Beginning with the 1875 Page Act, which targeted Chinese women for exclusion, the government passed a series of laws designed to stop non-white immigration to the United States. By 1924, Congress had adopted the Johnson-Reed Act, which banned nearly all Asian immigration and imposed a national origins system that slashed arrivals from southern and eastern Europe and imposed a new visa requirement which federal authorities used to block almost all Black immigration from European colonies in the Caribbean. White nationalists cheered the Johnson-Reed Act. “We have closed the doors just in time to prevent our nordic population being overrun by lower races,” declared one of the co-authors of the new law. However, the Johnson-Reed Act did not cap immigration from countries in the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Mexico. By 1929, most lawful immigrants to the United States arrived from Europe, Canada, and Mexico.

After Congress passed the Page Act, The Supreme Court issued a set of rulings that established the rules by which federal authorities could stop non-citizens from entering the country. Racial exclusion was at the center of these rulings. In Chae Chan Ping v. the United States (1889), the United States Supreme Court ruled that, as a matter of national security, Congress could impose rules to stop non-citizens from entering the United States for any reason, including their race.

Deportation and Due Process

In 1891, Congress passed a law to deport any immigrant who entered the United States but should have been excluded at the time of their entry. But Congress also imposed a one-year statute-of-limitations on most deportations, excluding Chinese laborers who, if they had unlawfully entered the United States, were indefinitely deportable. In 1903, Congress extended the general statute-of-limitations on most deportations to three years. In 1917, Congress extended this limit to five years.

Between 1876 and 1929, federal authorities recorded 116,445 deportations. Although most deportees were returned to Europe, the percentage of deportees who were European plummeted during the 1920s, especially after the establishment of the U.S. Border Patrol in 1924. By 1929, Mexicans comprised 22% of all deportees. Moreover, beginning in 1927, the Border Patrol created “Voluntary Departure” as an informal alternative to deportation, allowing Border Patrol officers to order undocumented Mexican and Canadian immigrants to “voluntarily” depart the country without the expense, consequence, and due process rights attached to a deportation hearing. Between 1927 and 1929, federal immigration authorities reported issuing 60,846 Voluntary Departure orders in comparison to 92,916 deportation orders. In time, Voluntary Departure would become the federal government’s primary method for ordering undocumented Mexican immigrants out of the country.

Immigrants subject to deportation and voluntary departure orders had limited access to due process and other constitutional protections. In Fong Yue Ting v. United States (1893), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Congress could authorize the deportation of non-citizens, and that it could do so without regard to constitutional protections formally required in the criminal system, such as trial by jury. The Court decided that “deportation is not a punishment for crime . . . It is but a method of enforcing the return to his own country . . . the provisions of the Constitution, securing the right of trial by jury, and prohibiting unreasonable searches and seizures, and cruel and unusual punishments, have no application.” In 1903, the Court made a small adjustment to the nation’s deportation rules, establishing that, unlike immigrants in exclusion proceedings at the nation’s borders, immigrants already residing in the United States were entitled to some due process, such as a hearing before removal, but those rights remained circumscribed and slim. According to a 1931 congressional study, the nation’s deportation system was “unconstitutional, tyrannic[al] and oppressive.”

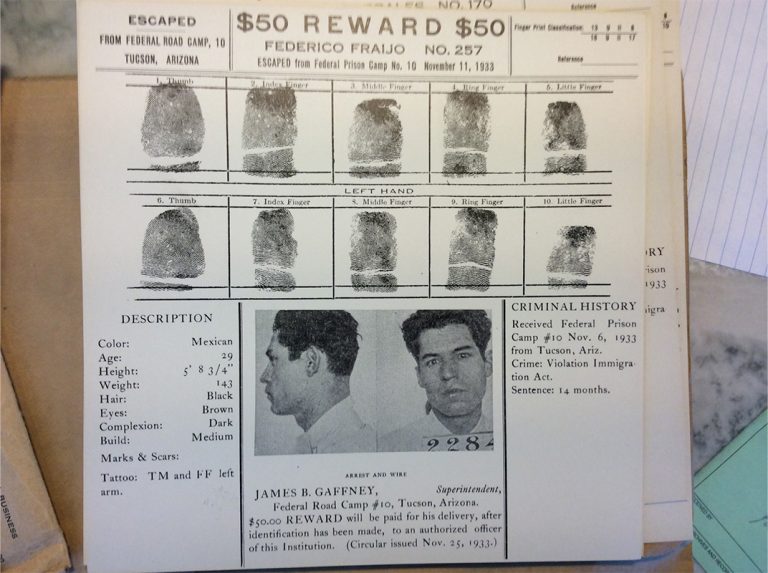

The Criminalization of Uninspected Border Crossings

In 1929, Congress made it a crime to enter the United States without inspection. At the time, white nationalists were demanding that Congress close the nation’s back door to Mexico. “The most dangerous mass immigration now menacing us is that from Mexico,” they warned after Congress adopted the Johnson-Reed Act, which banned Asian immigration and slashed Black immigration but left immigration from most of the western hemisphere numerically unrestricted. Employers in the American West wanted to keep the nation’s doors open to Mexico. Still, under pressure from eugenicists and other white nationalists, Congress opted to criminalize a popular entry method used by Mexicans: uninspected border crossings. In particular, the Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929 made it a federal misdemeanor to enter the United States without inspection, punishable by a fine and/or up to one year in prison, and a federal felony for migrants previously deported from the United States to reenter or attempt to reenter the United States without inspection, punishable by a fine and/or up to two years in prison. The criminalization of uninspected border crossings did not stop Mexican immigration to the United States, but it did criminalize many, if not most, Mexican border crossers. Since 1929, Mexicans and other nonwhite immigrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border have, by design, comprised the overwhelming majority of immigrants arrested, prosecuted, and imprisoned for unlawful entry/reentry.

Timeline of Key Events

Chinese Exclusion Act (May 6, 1882)

Immigration Act of August 3, 1882

Elk v. Wilkins (November 3, 1884)

John Elk (Ho-Chunk) was denied the right to vote in Nebraska on the ground that he was an “Indian,” even though he was born in the United States. He argued that he was a citizen under the Fourteenth Amendment because he was “born . . . in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” and therefore entitled to vote, especially because he had fully severed his relation to his tribe. The Supreme Court rejected his claim, holding that people born in (and as members of) “an independent political community” are not entitled to birthright citizenship. In 1924, Congress assigned citizenship to all Indigenous people born in the United States, effectively overruling Elk.

The Scott Act (October 1, 1888)

Chae Chan Ping v. United States (May 13, 1889)

The United States Supreme Court ruled that, as a matter of national security, Congress could impose rules to stop non-citizens from entering the United States for any reason, including race. As the Court explained, “The power of the legislative department of the government to exclude aliens from the United States is an incident of sovereignty . . . If, therefore, the government of the United States, through its legislative department, considers the presence of foreigners of a different race in this country, who will not assimilate with us, to be dangerous to its peace and security, their exclusion is not to be stayed because at the time there are no actual hostilities with the nation of which the foreigners are subjects.” The Supreme Court has never overruled Chae Chan Ping. On the contrary, courts continue to cite it as precedent to support broad claims of government power over immigration control, and even to engage in race discrimination at the border.

Immigration Act (March 3, 1891)

The 1891 Immigration Act expanded the list of banned immigrants to include “all idiots, insane persons, paupers or persons likely to become a public charge, persons suffering from a loathsome or a dangerous contagious disease, persons who have been convicted of a felony or other infamous crime or misdemeanor involving moral turpitude, polygamists, and also any person whose ticket or passage is paid for with the money of another or who is assisted by others to come . . .” This act also authorized the deportation of any immigrant who entered the United States but should have been excluded at the time of their entry and granted immigration officials the authority to order deportations without judicial review. But it imposed a one-year statute-of-limitation on most deportations, excluding Chinese laborers who, if they had unlawfully entered the United States, were indefinitely deportable. In 1907, Congress extended the general statute-of-limitation on most deportations to three years. In 1917, Congress extended this limit to five years. In 1952, Congress lifted nearly all statutes-of-limitation on deportation.

Nishimura Ekiu v. United States (January 18, 1892)

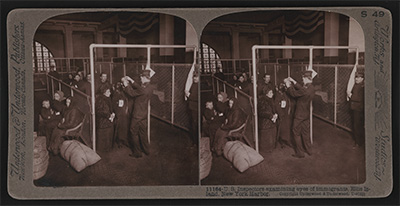

Ellis Island, est. January 1, 1892

Ellis Island opened as an immigrant processing and detention center. By 1954, federal authorities at Ellis Island had inspected nearly 12 million immigrants, mostly Europeans, fewer than 2% of whom were denied entry to the United States. In comparison, inspectors at Angel Island, California’s primary port of entry, denied entry up to 33% of the time to the mostly-Asian immigrants who sought entry between 1910 and 1940. To see a visualization of the number of admissions to the U.S. by region from 1899–1929, click here.

Geary Act (May 5, 1892)

Resistance Story

Chinese immigrants rebelled against the 1892 Geary Act, refusing to apply for the certificates and hiring some of the nation’s top lawyers to challenge its constitutionality. Could Congress really order people imprisoned and sent to hard labor without trial? And, where did the U.S. Constitution give the federal government the power to deport people—that is, banish them—from this country? In the years ahead, the Supreme Court would answer these questions in a set of rulings that left all immigrants with far fewer constitutional protections than the law had afforded them before. Several of these rulings remain precedent today.

Fong Yue Ting v. United States (May 15, 1893)

Fong Yue Ting and Wong Quan refused to comply with the 1892 Geary Act. Instead of registering with the federal government, they turned themselves in for arrest, while another long-term resident, Lee Joe, proved his residence with only a Chinese witness. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Fong, Wong, and Lee, upholding the “one white witness” rule on the ground that Congress not only could authorize the deportation of non-citizens, but could do so without providing the due process afforded to those facing punishment. “The right of a nation to expel or deport foreigners . . . rests upon the same grounds and is as absolute and unqualified as the right to prohibit and prevent their entrance into the country,” explained the Court. “The provisions of the Constitution, securing the right of trial by jury and prohibiting unreasonable searches and seizures, and cruel and unusual punishments, have no application [to deportation proceedings].” Based on that reasoning, it upheld the deportation of Chinese residents who had lived lawfully in the country for years, even though there was no evidence that they were unlawfully present. Although the Court would later extend limited due process rights to immigrants in deportation proceedings, Fong Yue Ting (1893) remains a foundational precedent widely cited in U.S. immigration law cases.

Fast Forward to Now

The Supreme Court has never overruled Chae Chan Ping, Nishimaru Ekiu, or Fong Yue Ting. On the contrary, courts continue to cite them as precedent to support broad claims of government power over immigration control, and even to engage in race discrimination at the border.

Wong Wing v. United States (May 18, 1896)

In re Rodriguez (May 3, 1897)

At the conclusion of the U.S.-Mexico War (1846-1848), the United States annexed what is now the American Southwest and, in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), extended U.S. citizenship to Mexicans living in this territory. In 1897, after two white men in San Antonio, Texas, claimed that Mexicans were racially ineligible to become naturalized U.S. citizens, a federal judge in Texas established that the United States was bound by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to honor Mexican eligibility for U.S. citizenship. Even if Anglo-Americans regarded many Mexicans as non-white in everyday life, Mexicans were to be regarded as “white by treaty” for the purposes of U.S. naturalization law. However, neither the treaty nor the Court’s ruling afforded citizenship (or other rights) to Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Diné, or other Indigenous peoples who continued to assert their own territorial and political claims in the region. To view a visualization estimating the proportion of deportation orders over time issued to Indigenous peoples, see here.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (March 28, 1898)

Fast Forward to Now

In one of his first major acts as President in 2025, Donald Trump attempted to reverse the Fourteenth Amendment's protections, declaring that children born to undocumented people and children born to immigrants here on temporary visas were not U.S. citizens. Immigrants' rights advocates and other have challenged this in the courts.

Immigration Act (March 3, 1903)

Yamataya v. Fisher (April 6, 1903)

Kaoru Yamataya, a Japanese immigrant in Washington, was arrested and ordered deported four days after entering the United States, on the grounds that she was likely to become a public charge. She challenged her deportation order, arguing that due process required that she receive adequate notice of the charges against her and a fair hearing. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees U.S. residents facing deportation—even those alleged to have entered illegally—the “opportunity to be heard upon the questions involving [their] right to be and remain in the United States.” Today, courts read Yamataya to establish that people facing deportation from within the U.S. (as opposed to those facing exclusion), have a right to a fair deportation hearing under the Constitution. However, Ms. Yamataya herself lost her case, as the Court ruled that she had not raised her objections (even though she did not speak English).

Fast Forward to Now

At least since the mid-1990s, the government and federal courts have steadily eroded the rule established in Yamataya by creating exceptions to its rule that individuals facing deportation from within the United States are entitled to a fair hearing. The Supreme Court approved one significant exception in DHS v. Thuraissigiam, which held that an individual arrested a short distance inside the United States could be treated like someone stopped at the border. Most recently, the second Trump administration has used the “expedited removal” power established in 1996 to deport thousands of individuals from within the United States without affording them a hearing before an Immigration Judge, despite Yamataya’s rule.

The Gentleman’s Agreement (February 15, 1907)

Under pressure from the Asiatic Exclusion League and similar groups, President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration reached a “Gentleman’s Agreement” with the Japanese government to stop most Japanese and Korean immigration to the United States.

In Their Own Words

Asiatic Exclusion League (1905)

Established in San Francisco, the Asiatic Exclusion League aggressively lobbied Congress to ban all Asian immigration to the United States. According to the League, “the Caucasian, Mongolian, Malay and Ethiopian can never dwell together in peace under the same fig tree.” It would largely succeed in its aims over the course of the next several decades.

Immigration Act (February 20, 1907)

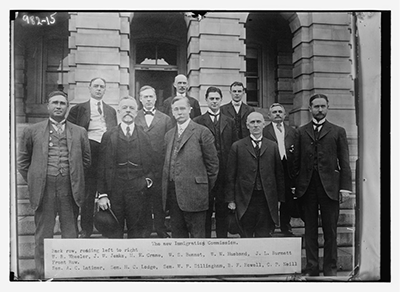

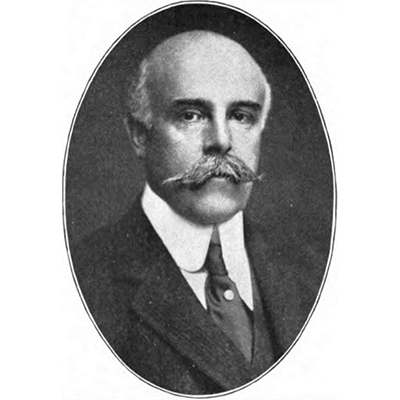

The 1907 Act extended the list of noncitizens prohibited from entering the United States to include “imbeciles, feeble-minded persons, epileptics and tuberculous aliens,” raised the head tax to $4, established that any noncitizen who entered the United States “except at the seaports thereof, or at such place or places as the Secretary of Commerce and Labor may from time to time designate, shall be adjudged to have entered the country unlawfully and shall be deported,” and created the first provisions authorizing deportation for post-entry conduct, such as criminal conviction. The 1907 Act also established the first bipartisan congressional committee to study immigration to the United States. Chaired by William P. Dillingham (R-VT), the committee became known as the Dillingham Commission. It would shape immigration law for decades to come.

Expatriation Act (March 2, 1907)

This law mandated that “any American woman who marries a foreigner shall take the nationality of her husband,” stripping U.S. citizenship from U.S. citizen women when they married non-citizen men. Since virtually all Asian immigrants were barred from becoming U.S. citizens at this time, this meant that white women who married Asian men would lose their citizenship.

Angel Island (January 21, 1910 - November 5, 1940)

Although dubbed the “Ellis Island of the West,” Asian immigrants arriving at the Angel Island immigration facility experienced radically different conditions than European immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. For example, Ellis Island arrivals were typically screened and released within 2-3 hours of arriving. In contrast, Angel Island arrivals were often detained for weeks or months. Some remained detained on the island for up to two years.

Dillingham Commission (1911)

Hearings on the Restriction of Hindu Laborers (February 13, 1914)

Rise of Eugenics (1890s to 1920s)

In Their Own Words (1916)

Madison Grant - “The American Prophet of Scientific Racism”

An internationally-renowned eugenicist, Madison Grant (1865-1937) has been described as the “American prophet of scientific racism.” In 1916, Grant published his most-influential book, The Passing of the Great Race, which, among other things, argued that humans originating from northwestern Europe were the world’s “Master Race” and immigration trends to the United States were threatening the nation’s roots as a nation peopled by “Nordics” and their descendants. Theodore Roosevelt called The Passing of the Great Race a “capital book; in purpose, in vision, in grasp of the facts of our people most need to realize.” Adolph Hitler called it “my Bible.” Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, Grant played a major role in pushing Congress to adopt a series of immigration restrictions that aligned with his world view by closing the nation’s doors to everywhere but northwestern Europe.

Immigration Act (February 5, 1917)

Emergency Quota Act (May 19, 1921)

Cable Act (September 22, 1922)

Ozawa v. United States (November 13, 1922)

Thind v. United States (February 19, 1923)

Bhagat Singh Thind was a soldier in the U.S. Army and a veteran of World War I. On December 9, 1918, Thind became a U.S. citizen. Four days later, the U.S. Bureau of Naturalization revoked his citizenship on the ground that he was not “white.” Thind contested the revocation, arguing that as a high-caste Hindu from India, he was Caucasian and therefore eligible to naturalize. The Court rejected Thind’s argument, reiterating that the intention of the naturalization laws “was to confer the privilege of citizenship upon that class of persons whom the fathers knew as white.” The Court then held “white” should be interpreted “in accordance with the understanding of the common man,” and asserted that “the physical group characteristics of the Hindus render them readily distinguishable from the various groups of persons in this country recognized as white” including “children of English, French, German, Italian, Scandinavian, and other European parentage.” The Court also noted that the “congressional attitude of opposition to Asiatic immigration generally,” including India, supported its decision.

After Thind, the U.S. Bureau of Immigration began to retroactively revoke the citizenship of naturalized U.S. citizens of Indian descent. They denaturalized sixty-five people between 1923 and 1924.

Tod v. Waldman (November 17, 1924)

Szejwa Waldman and her children sought admission to the United States as Jewish refugees from Ukraine. The government denied their request, arguing that Ms. Waldman was illiterate and one of her children was likely to become a public charge due to disability (she was alleged to be “lame”). A lower court ordered them released, and the government appealed. The Supreme Court ruled the Waldmans were entitled to a new hearing because government officials had not clearly stated their reasons for excluding them, including whether or not the Waldmans were in fact religious refugees (which would exempt them from the literacy requirement). Waldman exemplifies the Court’s expansion of due process protections for arriving non-citizens during this period.

The Johnson-Reed Act, aka National Origins Act (May 24, 1924)

Reduced the number of quota immigrants allowed to annually enter the country to 155,000 and tweaked the quota equation to increase the percentage of quota slots reserved for northwestern Europeans. The 1924 Act also prohibited all “alien[s] ineligible for naturalization” from entering the United States. Since U.S. naturalization law continued to exclude Asians from the right to naturalize, this provision was designed to end Asian immigration to the United States. Congress did not impose a ban on Black immigration but the 1924 Act also required all immigrants seeking to enter the United States to first acquire a visa from a U.S. consular abroad and consular officials in the Caribbean began systematically denying visas to Black immigrants. Black immigration plummeted by 94%, dropping from 12,243 in 1924 to 791 in 1925. See our visualization showing the impact on Black migration here.

Fast Forward to Now

For the lasts several decades, anti-immigrant advocates have reprised many of the racist themes underlying the 1924 Act. Those voices have gained prominence in the last ten years, as Donald Trump has embraced much of their ideology and rhetoric. Among many other examples, now-President Trump has said repeatedly that immigrants are "poisoning the blood of our country." At the time of the 1924 Johnson Reed Act, Representative Albert Johnson, one of the two architects of the Act, "[a]dvocated for the 'principle of applied eugenics' to reduce crime by 'debarring and deporting' people." The Johnson Reed Act as a valiant effort to exclude the "foreign body" of "strangers to the blood" of the ruling race.

U.S. Border Patrol (est. May 28, 1924)

On May 28, 1924, Congress established the U.S. Border Patrol. In the U.S.-Mexico border region, Border Patrol officers quickly focused on apprehending and deporting Mexican nationals.

House Hearing on “The Racial Problems Involved in Immigration from Latin America and the West Indies to the United States” (March 3, 1925)

Following the adoption of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, eugenicists demanded ending the western hemisphere exemption. Among them, the U.S. Secretary of Labor, James F. Davis, believed the western hemisphere exemption to the national quota system was “disastrous” because it did not cap non-white immigration from the Americas. In 1925, he commissioned a report, warning that “Immigrants from these countries [in Latin America and the West Indies] tend to lower the average of the race value of the white population of the United States.”

In Their Own Words

1925 - Senator Coleman Livingston Blease (D-SC)

After serving as the governor of South Carolina, Senator Coleman Livingston Blease (D-SC) was elected to Congress in 1925. He entered Congress with one goal: protect white supremacy. As a senator, he opposed the idea of a world court because he refused to support any “court where we [Anglo-Americans] are to sit side by side with a full blooded ‘nigger’.”; he read the poem, “N-----s in the White House,” from the floor of congress; and, he openly advocated for lynching. During a congressional debate over the western hemisphere exemption, Blease proved himself a strong proponent of ending the western hemisphere exemption. According to Blease, “I want them [Mexicans] kept out . . . When they get over here they have to behave or we will kill them.”

U.S. House Hearing on Seasonal Agricultural Laborers from Mexico (January/February, 1926)

In 1926, Rep. Albert Johnson (R-WA) held hearings on a proposal to end the Western Hemisphere exemption. The debate focused on stopping Mexican immigration to the United States. According to Rep. John C. Box (D-TX), “The continuance of a desirable character of citizenship is the fundamental purpose of our immigration laws. Incidental to this are the avoidance of social and racial problems, the upholding of American standards of wages and living, and the maintenance of order. All of these purposes will be violated by increasing the Mexican population of the country.” But diplomats and employers from the southwestern United States continued to oppose imposing the quota system on Mexico and prevented the proposal from advancing beyond hearings in the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization.

The Invention of Voluntary Departure (1927)

Facing a budget crisis, the U.S. Immigration Service authorized Border Patrol officers to offer Mexican and Canadian immigrants facing deportation the option to “voluntarily depart” to their home countries. By selecting “Voluntary Departure” (VD) instead of deportation, immigrants avoided detention and a formal deportation hearing, and the U.S. Immigration Service saved the time and money they would have otherwise had to spend on detention and formal deportation proceedings. Since 1927, over ninety percent of all forced removals out of the United States have occurred via the Voluntary Departure, also known as “Voluntary Return,” process. Historians estimate that Mexicans have typically comprised over ninety percent of all Voluntary Departures/Returns. To see a visualization showing the breakdown of voluntary departures by region, see our “Voluntary” Departures visualization.

U.S. House Hearings on the “Eugenical Aspects of Deportation” (February - April, 1928)

In 1926, Rep. Albert Johnson held hearings on a proposal to end the Western Hemisphere exemption. The debate focused on Mexican immigration. According to Rep. Box (D-TX), “The continuance of a desirable character of citizenship is the fundamental purpose of our immigration laws. Incidental to this are the avoidance of social and racial problems, the upholding of American standards of wages and living, and the maintenance of order. All of these purposes will be violated by increasing the Mexican population of the country.” But diplomats and employers from the southwestern United States continued to oppose imposing the quota system on Mexico and prevented the proposal from advancing beyond hearings in the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization.

U.S. State Dept. Begins Denying Visas to Mexican Workers (January 1929)

Registry Act (March 2, 1929)

The Registry Act allowed immigrants who had unlawfully entered the United States prior to June 3, 1921 to pay a $20 fee [$376 in 2025 dollars] and become Lawful Permanent Residents (LPRs). By 1940, Europeans and Canadians comprised 80% of the 115,000 immigrants who regularized their status through the Registry Act.

Fast Forward to Now

Registry functioned as a consistent legal pathway to give immigrants a way to regularize their status for many years, but has become less relevant over the last several decades as Congress has chosen not to update the eligibility date. Even today, the immigration laws permit individuals who came to the United States prior to January 1, 1972 to simply “register” for lawful permanent residence. Immigrants’ rights groups proposing “comprehensive immigration reform” in recent years have advocated updating the registry to implement that change.

Undesirable Aliens Act (March 4, 1929)

Fast Forward to Now

In 2021, a federal court ruled the illegal reentry statute unconstitutional because it was adopted with "discriminatory intent" and continues to disparately impact Latinos. The Biden administration appealed the ruling, and in 2023 the Ninth Circuit ruled in favor of the government. Courts have sided with the government in similar challenges elsewhere. Today, the federal government continues to aggressively prosecute the crimes invented by white nationalists in 1929. In 2022, 95% of people charged under Section 1326 were from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean countries.