1955-1990

Amend and Enforce

The Unanticipated Rise of Nonwhite Immigration

Between 1953 and 1990, legal immigration from Asia, Mexico, and Central America increased dramatically. The rise of lawful nonwhite immigration to the United States began after Congress passed the 1965 Immigration Reform Amendment (IRA), which prohibited racial discrimination in the nation’s visa allocation system. But the 1965 IRA did not purge racism from the immigration regime. For example, the 1965 IRA only banned discrimination in the nation’s visa allocation system, not the visa eligibility system. The visa allocation system only applies to immigrants who meet the basic eligibility requirements for lawful entry into the United States. In 2018, the Supreme Court used the distinction between admission eligibility and visa allocation to sanction the first Trump administration’s ban on immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries. After 1965, federal authorities also expanded the enforcement system designed to target, punish, and expel non-white immigrants. And, by replacing the 1920s national quota system with a “family-preference” system that gave priority to immigrants with relatives already living in the United States, many legislators expected that the 1965 IRA would not result in significant changes to immigration patterns. As Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) put it: “The ethnic mix of this country will not be upset.” However, few Europeans immigrated to the United States after 1965. In contrast, wars, political violence, and the prospect of economic opportunity drove millions of people from Asia, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to migrate in search of work and refuge. By 1985, immigrants from Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean constituted 80% of all legal immigrants to the United States.

Expanded Enforcement

As lawful nonwhite immigration to the United States increased after 1965, federal authorities expanded the nation’s immigration enforcement regime, which had been built over decades to remove non-white immigrants from the United States. The U.S. Border Patrol steadily expanded its deportation capacity during the 1940s and 50s, increasingly focusing its attention and resources on removing undocumented Mexican immigrants from the United States. Whereas Mexicans comprised 51% of all deportees in 1930, by 1954, when the Border Patrol unleashed its now-infamous “Operation Wetback” campaign, Mexicans comprised 84% of all deportees. In 1975, after several decades in which the Border Patrol had focused almost exclusively on deporting Mexican nationals, the U.S. Supreme Court declared “Mexican appearance” to be a legitimate indicator of unlawful status, sanctioning the Border Patrol’s racially targeted policing of Mexican immigration.

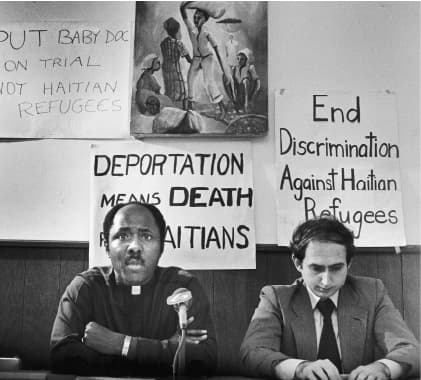

Meanwhile, during the 1970s, federal authorities responded to a sudden increase in Haitian refugees arriving in South Florida by detaining them, denying their asylum claims, and quickly deporting them. A federal judge called this a “transparently discriminatory” effort to stop “the first substantial flight of black refugees from a repressive regime to this country.” Soon after, migrants fleeing civil wars in Central America faced similarly discriminatory mistreatment.

During this period, Congress passed the Refugee Act in 1980, codifying the U.S. commitment to asylum into law, and adopted the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which offered legal status to nearly three million undocumented persons in 1986, most of whom were Mexican. But Congress also poured more and more resources into the nation’s deportation machine. Therefore, even as the United States experienced a historically-unprecedented surge of free and lawful immigration from Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Caribbean, the number of immigrants being removed from the United States exploded, with almost all of them being deported to Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

The Rebirth of Immigration Detention

Under President Eisenhower, the government announced an end to immigrant detention in virtually all cases. The Attorney General called it “a step forward toward humane administration of the immigration laws.” That commitment lasted until Haitian refugees began arriving in South Florida during the 1970s. Federal immigration authorities subjected almost all Haitian asylum seekers to mandatory detention. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court issued a set of rulings that granted federal immigration authorities the power to indefinitely detain people seeking admission if they presented a security threat, and to detain immigrants simply because they were allegedly dangerous, which in the 1950s often meant communists. The new Court rulings and the rebirth of immigrant detention to cage Haitian asylum seekers laid the groundwork for the rise of mass detention at the end of the century.

Timeline of Key Events

End of Guestworker Programs (December 31, 1964)

Between 1942 and 1964, more than 2 million immigrant workers from Mexico and the British West Indies entered and exited the United States on short-term labor contracts. The contracts had provided meaningful economic opportunities to many workers, but the programs had also been marked by labor exploitation and abuse, which led many workers, labor organizers, religious organizations, and others to oppose them. In 1964, Congress terminated these guestworker programs.

Immigration Reform Amendment (October 3, 1965)

The 1965 Immigration Reform Amendment abolished the 1924 national origins system and the “Asia Pacific Triangle” by establishing that “no person shall . . . be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of his race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence.” However, the 1965 IRA adopted a new quota system that reserved 74% of all immigrant visas for the immediate family members of U.S. citizens and permanent residents. At a time when Europeans comprised 75% of all immigrants living in the United States, the law’s authors expected family migration to privilege immigrants from Europe. As the law’s co-author, Representative Emanuel Celler (D-NY), put it: “since the people of Africa and Asia have very few relatives here . . . [there is] no danger whatsoever of an influx from the countries of Asia or Africa.” That prediction would prove to be wrong.

The 1965 Act also set a 170,000 cap on the number of immigrants allowed to enter the United States from the eastern hemisphere and established the first-ever quota for the Western Hemisphere, setting a 120,000 cap on the number of immigrants allowed to enter the United States annually from the Western Hemisphere. In 1964, more than 200,000 Mexican immigrants had legally entered the United States, meaning that the new western hemisphere quota cut legal immigration from Mexico by at least 60%. U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions surged from 52,422 in FY1965 to 812,541 in FY 1977, as labor migration from Mexico continued following the implementation of the western hemisphere quota.

Cuban Adjustment Act (November 2, 1966)

United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (October 4, 1967)

Fast Forward to Now

The Protocol’s promise of non-discrimination in refugee admissions remains unfulfilled. U.S. refugee policy has consistently favored some groups over others based on race, political alignment, and other factors despite the Protocol. Disfavored refugee groups—such as Haitians (relative to Cubans) and Afghans (relative to Ukrainians) have challenged such their discriminatory treatment from time to time, but the Supreme Court has never found it unconstitutional. Most recently, a group of white South African Afrikaners arrived in the U.S. under a new Trump administration refugee program which fast-tracked their admission shortly after indefinitely suspending all other U.S. refugee programs.

United States v. Brignoni-Ponce (June 30, 1975)

Brignoni-Ponce sanctioned the Border Patrol’s use of “Mexican appearance” as a relevant factor in deciding to stop cars or interrogate people in the 100-mile border zone. It helped to facilitate Border Patrol’s on-going role in deporting both recent and long-established Mexican migrants from the border region.

Fast Forward to Now

Brignoni-Ponce’s rule that race could be considered by immigration enforcement agents when deciding whether to stop vehicles and detain people for further questioning has been sharply limited in subsequent lower court decisions. Those cases have generally found that shifting demographics (as Latinos have become a larger share of the population) and changing legal doctrine concerning the use of race have altered the legal landscape concerning the use of race. Nonetheless, there is strong evidence that immigration officials continue to use race when determining whom to target for immigration enforcement. A federal judge in Los Angeles recently ruled that agents were likely doing exactly that during large-scale enforcement operations taking place throughout the greater Los Angeles area.

Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act (May 23, 1975)

Authorized amid the fall of Saigon in 1975, the Gerald Ford administration began “paroling” Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian immigrants as well as members of the Hmong community (from both Vietnam and Laos) into the United States. The Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act allocated $155 million in resettlement aid for up to 135,000 refugees from the region. By 1987, more than 750,000 refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos had been resettled in the United States.

Immigration and Nationality Act Amendment of 1976

Immigration and Nationality Act Amendment of 1978

The Haitian Program (1978 - 1981)

Fast Forward to Now

Three years ago, newspapers around the country published pictures of a white man on horseback chasing and grabbing at fleeing black men on a grassy hill, apparently using a whip. The image evoked scenes from a slave plantation, but the man on the horse wore a green Border Patrol vest. He was in Del Rio, Texas, where the federal government was in the process of deporting thousands of Haitians who had come to the U.S. seeking refuge. The White House and Congressional Democrats quickly condemned the “horrific” images. Within days, they had stopped the Border Patrol from using horses in Del Rio. But they did not stop the deportations. Over the next several months, the government would expel 20,000 refugees to grave danger in Haiti. Most of them were denied the opportunity even to ask for asylum.

The Federation for American Immigration Reform (1979 - present)

Fast Forward to Now

In 2017, SPLC also designated the Center for Immigration Studies, one of FAIR’s sister organizations, as a hate group. Nonetheless, several people who worked on immigration policy for the first and second Trump administrations previously worked with FAIR, CIS, or one of their affiliated organizations.

Refugee Act (March 17, 1980)

The Act defined a “refugee,” in accordance with the Refugee Convention, as any immigrant who cannot stay within or return to their home country “because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” It also prohibited the federal government from deporting refugees, established a uniform process for people to apply for refugee status, and set aside 50,000 non-quota visas for refugees while allowing the president to exceed this limit in cases of “grave humanitarian concern.” The law promised to end nearly two hundred years of race discrimination in humanitarian admissions, but federal authorities broke that promise within a month, again targeting Haitian immigrants for detention and removal. Meanwhile, the departments of State and Justice also denied refugee status to migrants from El Salvador, who began arriving in the United States in large numbers in late 1979, following the outbreak of a brutal civil war in which the United States backed a right-wing government that engaged in acts of extraordinary political violence that a United Nations Truth Commission would later declare to be “war crimes.”

Mariel Boatlift (April - October 1981)

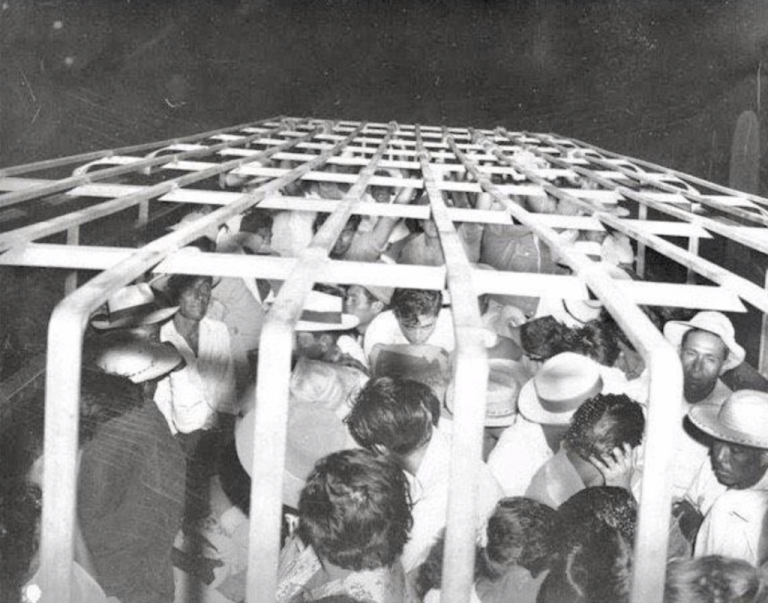

In April 1980, Fidel Castro began allowing Cubans to leave the country. By September 1980, nearly 100,000 Cubans had arrived in South Florida; nearly 15,000 Haitians also arrived in the spring of 1980. Although the Carter administration paroled most Haitian and Cuban migrants into the United States, Haitians, who continued to arrive in large numbers, were jailed for months(—)sometimes years(—)at a swampy decommissioned missile site in Florida (known as Krome Detention Center) and, later, at a retired army base in Puerto Rico.

Fast Forward to Now

During the 2024 campaign, then-candidate Trump consistently repeated an assertion that other countries, including Venezuela, were “emptying their prisons” and mental hospitals to send people to the U.S. These statements, while thoroughly debunked, echo those made by anti-immigrant politicians going back at least one hundred years. Many people to this day believe the claim was true when President Jimmy Carter and others suggested that most of the Cuban refugees who arrived on the Mariel boatlift were released by Fidel Castro from Cuban prisons. Detailed reporting has uncovered that those claims were largely overstated.

Haitian Refugee Center v. Civiletti (July 2, 1980)

Executive Order 12324 - Interdiction of Illegal Aliens (September 29, 1981)

This order authorized the interdiction of ships carrying undocumented immigrants on the high seas. The order targeted Haitian migrants attempting to arrive in the United States and petition for asylum. Between 1981 and 1990, the U.S. Coast Guard interdicted 22,940 Haitians at sea. According to the INS, only 11 of the Haitians interdicted at sea were eligible to apply for asylum in the United States. The Supreme Court upheld this practice in Sale v. Haitian Refugee Center, thus paving the way for many interdiction practices the government has utilized since.

Mandatory Detention for All Asylum Seekers (July 1982)

Jean v. Nelson (June 26, 1985)

Despite the 1980 Civiletti ruling, the Carter and then Reagan Administrations continued to pursue the policy of detaining and deporting Haitian refugees, and the issue eventually reached the Supreme Court in Jean v. Nelson. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the refugees on technical grounds but left open whether the Constitution prohibits the government from engaging in race discrimination in immigrant admissions.

Fast Forward to Now

In Florida, the Eleventh Circuit has since reaffirmed its earlier rule permitting race discrimination in exclusion policy, thus allowing the government to treat Haitians more harshly than other migrants. In this sense, the Chinese Exclusion cases remain alive to this day.

Anti-Drug Abuse Act (October 27, 1986)

Immigration Reform and Control Act (November 7, 1986)

Focused on the issue of illegal immigration, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) offered legal status to long-term undocumented residents, imposed sanctions on employers for hiring undocumented workers, and increased funding for the U.S. Border Patrol. It didn’t work. The legalization programs resulted in 2.7 million immigrants becoming lawful permanent residents, but nearly as many undocumented immigrants either missed the application deadline or did not qualify for the amnesty programs. Federal authorities proved unwilling to enforce the employer sanctions. And funding for the U.S Border Patrol enhanced the agency’s capacity to apprehend, detain, and deport immigrants but, as the costs and dangers associated with undocumented entry skyrocketed, migrants remained in the United States rather than traveling seasonally between home and work. In the end, IRCA created a one-time amnesty program while making permanent investments in border enforcement, which actually increased the size of the undocumented population living in the United States.

IRCA also established two new programs—the diversity lottery and the visa waiver program—that propped the nation’s door open to immigrants from Europe and white settler nations. The diversity lotto set aside 10,000 visas for nationals “born in” countries “adversely affected” by the 1965 Act. According to Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA), the diversity lottery was a way to resolve “unforeseen problems” following the 1965 Act, which had restricted immigration from European countries, which Kennedy described as the “old seed sources of our heritage.” Originally, Congress reserved 40% of the visas for Irish immigrants and, until 2001, European immigrants took most of the visas. Since then, African immigrants have increasingly used the program to access visas and enter the United States. Meanwhile, the visa waiver program allowed individuals from designated countries to enter the U.S. without needing to obtain a visa for a period up to 90 days. As of 2024, 36 of the 41 countries are located in Europe or are white settler societies.

Anti-Drug Abuse Act (November 18, 1988)

The 1988 ADAA was a significant law passed as part of the War on Drugs. Among other things, it restored the federal death penalty and imposed a mandatory minimum of five years in prison for simple possession of 5g or more of crack cocaine. The 1988 Act also created a new category of crime called “aggravated felonies,” which only applies to non-citizens, establishing that non-citizens convicted of crimes defined as aggravated felonies were subject to mandatory detention and expedited deportation upon the completion of their sentence. In other words, the 1988 ADAA made immigration detention and deportation the virtually-inevitable result of certain criminal convictions, creating a template that Congress would use to dramatic effect in the 90s. The ADAA also increased the maximum sentence to fifteen years for an illegal reentry conviction with a prior aggravated felony.

Immigration Act (November 29, 1990)

The first and last major overhaul of the legal immigration system since 1965, the 1990 Act made numerous changes to the immigration system. In particular, it substantially raised the annual cap on the number of quota immigrants allowed to enter the United States each year from 390,000 to 675,000. But, the 1990 Act offset the total increase in quota immigration by deducting up to 254,000 slots from the total quota depending upon the number of immigrants who entered the United States the previous year as the immediate relatives (spouse, parents, and unmarried minor children) of U.S. citizens. In particular, if more than 254,000 non-quota immigrants entered the United States as the immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, the next year’s quota allocation for the family preference was reduced by 254,000 slots. Since the number of non-quota immigrants has typically exceeded 254,000 annually, the functional annual maximum for quota immigration to the United States, as set by the 1990 Immigration Act, is 421,000 visas, not 675,000, with 226,000 visas reserved for the family preferences, 140,000 visas reserved for employment, and 55,000 visas for the diversity lotto.

The 1990 Act also created the humanitarian relief program known as Temporary Protected Status (TPS). Like the 1980 Refugee Act, the TPS program was designed to create objective, non-discriminatory criteria for the government to apply when determining which countries warranted broad-based humanitarian protection. Congress designated immigrants from El Salvador as the first TPS recipients and, since then, has extended TPS to a wide range of immigrants from Central America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. Notably, although many TPS holders have found ways to obtain permanent resident status, the 1990 Immigration Act did not provide a direct pathway to legal permanent status for TPS holders.

The 1990 Act also leaned into enforcement by expanding the category of “aggravated felonies” to include crimes of violence for which the term of imprisonment imposed is at least five years. Within just a few years, Congress would again expand the aggravated felony category to encompass many non-violent offenses, thereby tightly linking the U.S. immigration control and criminal legal systems.

Ultimately, the 1990 Act reflected a compromise between those favoring more immigration and respect for human rights and those seeking to stoke European immigration to the United States.