1930-1954

Consolidate and Carry Forward

Amending the Whites-Only Immigration Regime

World War II forced Congress to amend the whites-only admissions system. China, a wartime ally, successfully pressured Congress to end Chinese Exclusion. Restrictions on most of Asia were lifted shortly afterwards. And, the federal government facilitated the entry of West Indian and Mexican laborers to fulfill war and post-war labor demands. But, when Congress passed the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which consolidated various provisions into one comprehensive set of immigration rules, it designed the national origins system to strictly cap Black and Asian immigration to the United States while the government’s labor importation programs placed most Mexican and Black migrants arriving in the United States in the category of short-term contract laborer, restricting them to the “non-immigrant” status known as “guestworker.” In these years, U.S. officials also introduced racial exclusion in humanitarian admissions by framing the U.N. Refugee Convention to permit nations to choose to protect only European refugees. The U.S. admitted several hundred thousand European war refugees in this period.

Targeting Mexicans for Expulsion

When the Great Depression began, local and state authorities pressured Mexican immigrants to leave the United States. By 1940, hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants and their U.S.-born children had left the country. Then, as World War II came to a close, the U.S. Border Patrol conducted widespread deportation operations that targeted undocumented Mexican immigrants for expulsion, culminating in Operation Wetback of 1954, during which the United States Border Patrol reported expelling more than 1 million undocumented Mexican immigrants from the United States.

No comparable expulsion campaigns targeted European and Canadian immigrants during this period. If anything, the federal government made it easy for undocumented Canadian immigrants to legalize their status. For example, federal authorities developed an informal “pre-examination” program that allowed undocumented Canadian and European immigrants to return to Canada, pick up a pre-arranged visa, and return to the United States as a lawful permanent resident. By 1950, tens of thousands of unlawful Canadian immigrants had used the program to adjust their status. The 1952 INA, Congress revised and codified the pre-examination program, making it possible for undocumented immigrants who had originally entered the United States on a visa to adjust their status without having to leave the United States. But the 1952 INA categorically banned immigrants who entered the United States without inspection (Mexican) from participating in the program.

Also, although Congress had abolished explicit racial restrictions in the U.S. naturalization code, the 1952 INA also made undocumented immigrants more vulnerable to deportation by lifting nearly all statutes-of-limitation on deportation.

Prosecuting Undocumented Border Crossers Anywhere in the Country

During this period, the Department of Justice prosecuted more than 100,000 immigrants for unlawful entry/reentry. In 1952, the INA made those crimes faster, easier, and cheaper to prosecute. For example, whereas the 1929 legislation had only criminalized “entering” or “attempting to enter” the United States without inspection, the INA expanded felony reentry to include the acts of “entering,” “attempting to enter,” or being “found in” the United States without inspection, allowing immigration agents to apprehend migrants anywhere in the country and prosecute them locally for felony reentry.

Timeline of Key Events

Tydings-McDuffie Act (March 24, 1934)

The Tydings McDuffie Act ended unrestricted immigration from the Philippines, which had been a U.S. territory since 1899, by promising independence to the Philippines in 1945 and immediately limiting Filipino immigration to no more than 50 people annually.

Alien Registration Act (June 28, 1940)

A wartime measure, the Alien Registration Act made it a crime for anyone to “knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises, or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association.” This 1940 law also required all adult non-citizen residents of the United States to register with the federal government within four months. This short-term registration requirement was permanently codified in 1952, although it has been inconsistently enforced.

Fast Forward to Now

The second Trump Administration has attempted to aggressively enforce this law, creating a scheme that requires large classes of non-citizens, including undocumented people, to register. Those who fail to register can be prosecuted, thus effectively rendering it a crime to be undocumented. Immigrants’ rights groups have challenged the program in court.

Nationality Act (October 14, 1940)

WWII Farm Laborer Programs (1942-1964)

The U.S. signed “non immigrant” labor agreements with Mexico and the British West Indies. These agreements allowed contract workers from Mexico, the Bahamas, Jamaica, Barbados and British Honduras (now Belize) to enter the United States, work on farms across the United States, and return home at the end of their contract. Under these agreements, millions of Mexican and Caribbean laborers were authorized to temporarily work in the United States, but not permanently settle. The agreements, which formally assigned a large number of non-white labor migrants to temporary status in the United States, lasted between 1943 and 1964, and facilitated the arrival and departure of approximately 30,000 West Indians and more than 2 million Mexicans.

Magnuson Act (December 17, 1943)

In response to demands from advocacy groups who opposed Chinese exclusion as well as the government of China, a wartime ally, Congress lifted the naturalization ban for Chinese immigrants, which made Chinese immigrants eligible to enter the United States. But Congress subjected China to the quota regime, which capped Chinese immigration at no more than 105 Chinese immigrants per year.

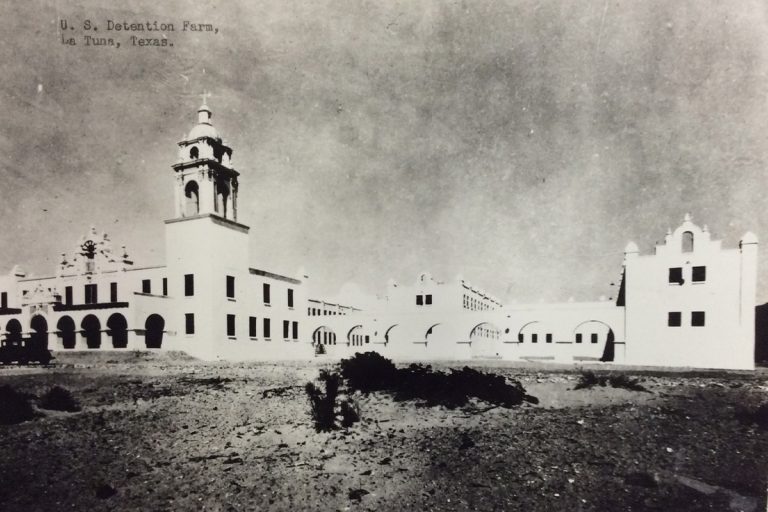

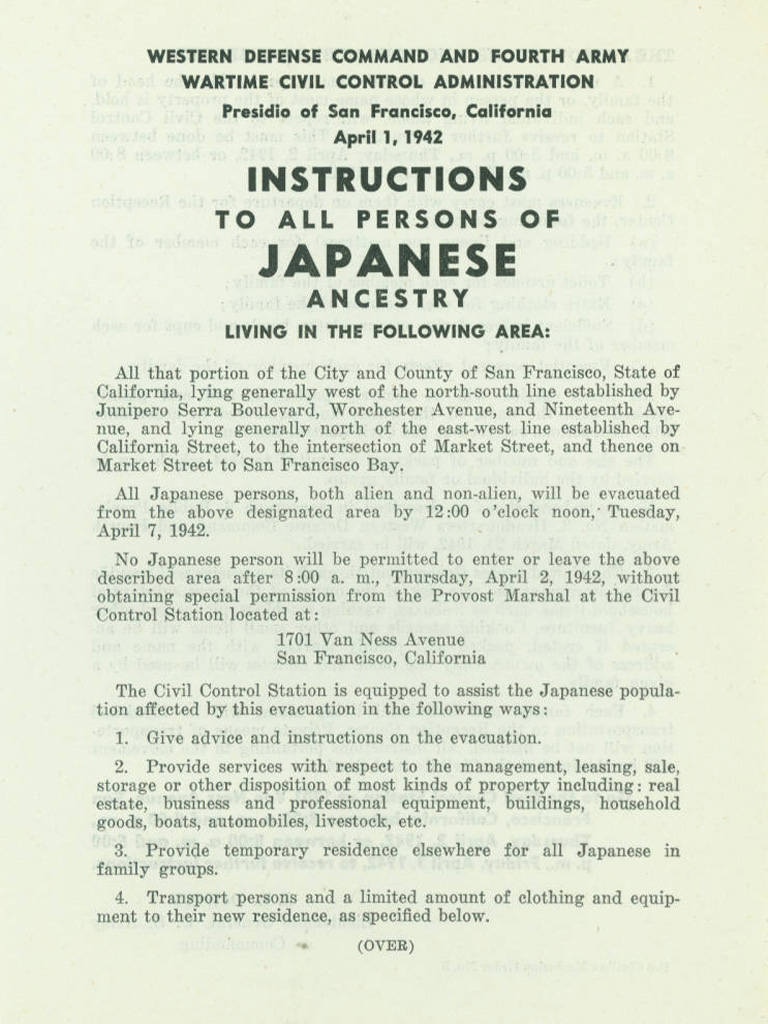

Korematsu v. United States (December 18, 1944)

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which ordered the mass incarceration without trial of both Japanese immigrants and U.S. citizens of Japanese descent living in the western United States. Fred Korematsu, a Japanese-American man from San Leandro, California, refused to comply with the order. When he was arrested and convicted for violating the order, he appealed his conviction. In Korematsu, the Court ruled that the conviction was valid, noting that the “military urgency of the situation” justified the evacuation of U.S. citizens on the basis of their race. The Court did not overrule Korematsu until 2018 when, in its decision upholding the Muslim Ban, the Court stated that Korematsu was no longer good law.

Luce-Celler Act (July 2, 1946)

The Displaced Persons Act (June 25, 1948)

Guam Organic Act (August 1, 1950)

This law lifted the naturalization ban on the Chamorro people from and residing in the U.S. territory of Guam.

The Immigration and Naturalization Systems of the United States: The Senate Report (1950)

Following a multi-year study of the nation’s immigration and naturalization laws, this senate report recommended maintaining the 1920s quota system. “Without giving credence to any theory of Nordic superiority,” explained the report “the subcommittee believes that the adoption of the national origins formula was a rational and logical method of numerically restricting immigration in such a manner as to best preserve the sociological and cultural balance in the population of the United States. There is no doubt that it favored the peoples of the countries of Northern and Western Europe over those of Southern and Eastern Europe, but the subcommittee holds that the peoples who made the greatest contribution to the development of this country were fully justified in determining that the country was no longer a field for further colonization and henceforth further immigration would not only be restricted but directed to admit immigrants considered to be more readily assimilable because of the similarity of their cultural background to those of the principal components of our population.” This report established the basis for the next major overhaul of the U.S. immigration regime: the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act.

Knauff v. Shaughnessy (December 16, 1950)

In October 1948, the Assistant Commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service and the U.S. Attorney General denied entry to Ellen Knauff, the German wife of a U.S. citizen. They did so without affording her a hearing, based on secret evidence that she presented a national security threat. Knauff appealed her exclusion, arguing that she had been excluded without due process. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Government’s favor, “swiftly demolish[ing] half a century of immigration jurisprudence” that had established limited due process protections for arriving non-citizens. In doing so it invented a new rule just for exclusion cases: “[w]hatever the procedure authorized by Congress is, it is due process as far as an alien denied entry is concerned.” To this day, courts and immigration authorities cite Knauff and related cases to “deny all but the most limited procedural protections to migrants who have not been inspected and legally authorized to enter the United States.”

The United Nations Refugee Convention (July 28, 1951)

The Convention defined a refugee as “any person who . . . as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” The Convention’s drafters gave states the option of limiting this definition to protect people displaced by “events occurring in Europe,” which several of them did. The United States did not adopt the Convention, despite having helped to write it.

Carlson v. Landon (March 10, 1952)

Resistance Story

David Hyun

David Hyun was one of the people who fought against his detention and deportation in Carlson v. Landon. Hyun, originally from Korea and a citizen of China, came to the U.S. at the age of seven, first arriving in Hawaii and eventually settling in California. Hyun served in both the Reserve Officers Training Corps at the University of Hawaii and the United States Engineer Corps. Despite his many equities, the government detained Hyun on the sole justification that his affiliation with the Communist party deemed him a danger to the U.S. The Supreme Court upheld his detention in Carlson v. Landon.

An act to assist in preventing aliens from entering or remaining in the United States illegally, aka The “Wetback” Bill (March 20, 1952)

Immigration and Nationality Act (June 27, 1952)

Consolidated, revised, and codified into a single code all immigration and naturalization laws passed since 1917. This 1952 law, which remains the basic framework for the U.S. immigration system, terminated the racial bar for naturalization but otherwise carried forward the whites-only immigration regime. In particular, the 1952 INA carried forward the national quota system and created an “Asia Pacific Triangle” as a global race quota applied to all persons of Asian descent. According to this quota, only 2,000 immigrants of Asian descent were allowed to enter the United States annually from anywhere in the world. Similarly, the 1952 INA removed the British colonies in the Caribbean from Britain’s large national quota and instead assigned each colony its own quota, allocating no more than 100 slots annually to the Black-majority British colonies in the Caribbean. These Caribbean caps refreshed the quota system to better restrict the number of Black immigrants allowed to enter the country every year.

The 1952 INA also revamped the criminal codes designed to punish Mexicans for entering the United States without inspection. Not only did the 1952 INA carry forward the 1929 crimes of entering and re-entering the United States without inspection but it broadened the codes and made them easier and cheaper to prosecute. Whereas the 1929 legislation had only criminalized “entering” or “attempting to enter” the United States without inspection, the 1952 INA also made it a felony for deportees to be “found in” the United States without inspection. With this expansion in the law, immigration officials could apprehend migrants anywhere in the country and prosecute them locally without having to transport a defendant to the border jurisdiction where they were accused of having entered the United States without inspection. It also effectively erased any statute of limitations for the crime. The 1952 Act also reduced the penalty for unauthorized entry from one year to six months, making it a petty offense, for which there is no right to a jury trial. The combined effect of these changes was to make the crimes of unlawful entry and re-entry far easier and cheaper to prosecute, thus strengthening the criminal prohibition originally enacted in 1929 to target Mexican immigrants.

The 1952 INA also ended the five-year statute of limitations for most deportations, including for immigrants who entered without inspection. At a time when Mexicans comprised over 90% of deportees, these changes to the nation’s deportation laws laid the foundations for a vast undocumented population that would be overwhelmingly Mexican. Congress passed these enforcement enhancements without debate.

Finally, the 1952 INA also granted the U.S. Attorney General the authority to temporarily “parole” into the United States an unlimited number of noncitizens “under such conditions as he may prescribe for emergent reasons or for reasons deemed strictly in the public interest any alien applying for admission to the United States.”

In sum, the 1952 INA not only retained the national origins system but tweaked it to curb Asian and Black migration, and made it faster, easier, and cheaper to prosecute Mexicans for entering or reentering the United States without inspection, while formalizing a parole system that, at the time, was almost exclusively used to admit European refugees into the United States.

President Harry Truman vetoed the 1952 INA. The law “discriminates, deliberately and intentionally, against many peoples of the world,” he wrote, urging Congress to continue revising the nation’s immigration code and, in particular, abolish the national origin system. But Congress overrode Truman’s veto. As the law’s author, Senator Patrick McCarran (R-NV) had warned, “If we scrap the national origins formula we will, in the course of a generation or so, change the racial complexion of the population of this nation.” A major victory for McCarran and other white nationalists determined to maintain the nation’s “racial complexion,” the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) updated and reinforced the whites-only immigration regime.

Fast Forward to Now

The 1952 law created the parole authority that now constitutes the basis for humanitarian parole. Despite the long history of parole and frequent use by presidents from both political parties, President Trump terminated a number of parole programs after his second inauguration in January 2025, claiming those programs exceeded the President’s authority. Immigrant rights advocates are challenging this in court.

Shaughnessy v. United States ex rel. Mezei (March 16, 1953)

Ignatz Mezei, the husband of a U.S. citizen who had previously resided in the U.S. for 25 years and was returning from travels to Hungary, was excluded upon returning to the U.S. on the same grounds as Knauff–on the “basis of information of a confidential nature, the disclosure of which would be prejudicial to the public interest.” In contrast with Knauff, Mezei could not leave the U.S. after being denied entry because no country would take him, so he remained detained at Ellis Island for 21 months when he challenged his exclusion and detention. Mezei’s prospect of indefinite detention did not change the Supreme Court’s calculus, however. In Mezei, the Court upheld his exclusion and detention, citing Knauff and Chae Chan Ping, reaffirming that the only due process required upon entry is what Congress establishes, and stating that the exclusion power is a “fundamental sovereign attribute . . . largely immune from judicial control.” Mezei made clear that the U.S. could exclude noncitizens with minimal process as defined by Congress, and also that the U.S. could indefinitely detain noncitizens in the course of their exclusion without violating due process protections.

Refugee Relief Act (August 7, 1953)

Provided an additional 209,000 special visas for European refugees fleeing Communist countries to enter the United States on a non-quota basis.

Whom We Shall Welcome, Report of the President’s Commission on Immigration and Naturalization (January 1, 1953)

This Commission established by President Truman to challenge the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act declared that the INA “should be completely rewritten.” The Commission also called for the “abolition of all deportation except where entry into the United States had been obtained by fraud.” Immigration restrictionists in Congress repeatedly stymied follow-up efforts to repeal and replace the 1952 INA.

100-Mile Border Zone (1953)

The U.S. Department of Justice issued a regulation establishing an expansive jurisdiction for Border Patrol officers to enforce the nation’s immigration laws, allowing them to, without a warrant, stop, search, and question people about their immigration status within 100 miles of any national boundary. Today, about 200 million people live within the Border Patrol’s 100-mile jurisdiction.

Closure of Ellis Island (November 12, 1954)

In 1954, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service closed Ellis Island, with the U.S. Attorney General declaring that the “humane administration of the immigration laws” requires the abolition of immigrant detention, except in cases of public safety and flight risks.” In other words, federal authorities abolished immigrant detention in 1954. The Immigration and Naturalization Service relaunched immigrant detention during the late 1970s to stop Haitian immigration to the United States.

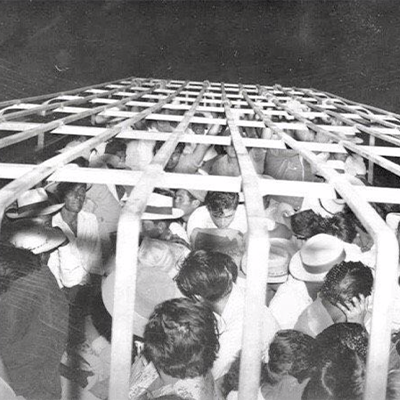

Operation “Wetback” (May - October 1954)

During the summer of 1954, the U.S. Border Patrol unleashed a mass deportation campaign. Targeting Mexican immigrants who had unlawfully entered the United States, the Border Patrol used paramilitary tactics to apprehend large groups of Mexican immigrants across the southwestern United States. By the end of FY 1954, the Border Patrol reported conducting more than 1 million deportations or other forcible removals, prompting the Immigration and Naturalization Service to declare, “the era of the wetback is over.”

Fast Forward to Now

For several years, President Trump has called for a mass deportation program modeled on this 1954 campaign. He began to implement such a program in Los Angeles in the summer of 2025, carrying out widespread warrantless arrests by masked federal agents on the street, at car washes and other businesses, and in Home Depot parking lots. Immigrant rights advocates are challenging this practice of widespread, warrantless arrests devoid of individualized suspicion in court.